Exhibition on the ground floor of 12 Piccadilly Arcade, SW1

-

-

Alastair Gordon, A New Beginning, 2021

Alastair Gordon, A New Beginning, 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, B Flat, 2021

Alastair Gordon, B Flat, 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, Improvisation, 2021

Alastair Gordon, Improvisation, 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, 'Jacob's Dream', 2019

Alastair Gordon, 'Jacob's Dream', 2019 -

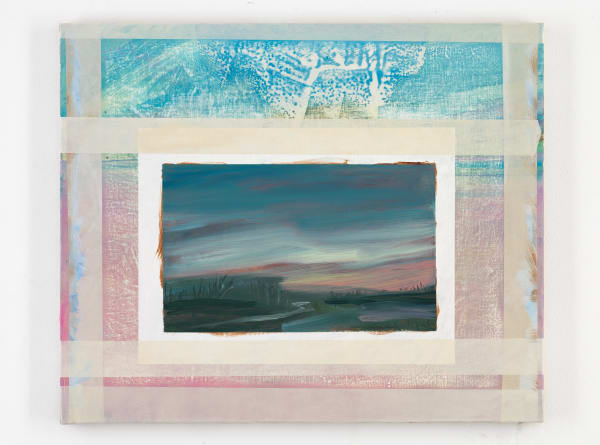

Alastair Gordon, Pink Dawn , 2021

Alastair Gordon, Pink Dawn , 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, The Bewitching , 2021

Alastair Gordon, The Bewitching , 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, Through A Glass Darkly , 2021

Alastair Gordon, Through A Glass Darkly , 2021 -

Alastair Gordon, Study For Jacob's Dream, 2021

Alastair Gordon, Study For Jacob's Dream, 2021

-

-

Alastair Gordon: Quodlibet

The curious, wondrous genre of quodlibet painting, like all trompe l’oeil, hinges on the mechanics of surprise. An initial deception - painting deceives us into believing it is reality rather than painted illusion - gives way to realization of the deception and the ensuing surprise. But it is what follows this momentary confusion and astonishment that matters. That is, how the trompe l’oeil invites an interrogation, one that is above all metaphysical, into questions of truth and reality, the nature of objects as signs, the conditions of artmaking and the limits and potentials of painting as a form of representation. Here, painting is not a window on to the world, but an inquiry into painting which, through the juxtaposition of profundity and banality poses itself as a puzzle. In Jean Baudrillard’s memorable words, it is by ‘outdoing the effect of the real’ that the trompe l’oeil throws ‘radical doubt on the principal of reality’.

In the visual arts, ‘Quodlibet’ customarily names a particular type of trompe l’oeil composition that came to prominence in 18th century Northern Europe - typically of a cluster of domestic objects, including letters and printed matter, held fast with tapes to a wooden panel. To the questions of illusionism and simulacrum that characterizes all trompe l’oeil, the quodlibet brings the dimensions of intimacy, privacy, sometimes even secrecy. Not only are the objects depicted apparently the objects of an individual’s private bureau or studio, offering a glimpse into the artist’s private life including the working methods usually kept hidden from view, or confidences such as political allegiances. We are made to feel as though we have by chance stumbled across a scene not intended for our gaze – although of course nothing in these compositions is left to chance.

Alastair Gordon reinvents the quodlibet genre for our contemporary times. Like their 18th century predecessors, these are paintings that show the artists’ mastery of illusion and visual trickery. They retain too many of the traditional formal devices – the presence of paper, sometimes folded, curled or crumpled, the pinned objects to a board or wall; the inclusion of the devices of fastening – blue-tack or masking tape – which functions to intensify the deception, since, through the framing within a frame, these devices further confuse the boundaries of the real and invite physical engagement, to test the threshold of reality through touch.

The presence of the painted masking tape is a particularly notable feature of Gordon’s works. At times it acts to tape bits of paper to the board. Sometimes it acts as a border - in Through a glass darkly, tape lines the four edges of the painting, as well as tacking the painting of a landscape to the ‘board’. At other times, the tape seems to have no function – we see bits of tape still tacked to the ‘board’, as though forgotten. This is particularly prevalent in Jacob’s Dream, where the yellow and white strips of tape create a formal rhythm of their own, an abstract composition alongside the figuration. This abstraction is seen in powerfully reduced form in ‘Study for Jacob’s dream’ , in which a torn piece of white paper is tacked onto a torn piece of yellow paper, which is taped to a panel painted loosely in blue. Here, the preparation of painting is at once part of a meta-commentary whilst also functioning as a geometric abstraction.

The subject of Gordon’s quodlibets are all paintings, presented in various stages of completion (but never in a finished state). The compositions present as snapshots of the artist’s studio, glimpses of sections of the studio wall, complete with stains and blotches, colour tests, taped source material (postcards and other ephemera), drawings and preparatory sketches and sometimes objects, such as the twigs in ‘Improvisations’, or ‘accidental’ incursions, such as the artist’s cat. These works are also comments on the nature of the artist’s studio, and the modesty, perhaps even the banality, of the everyday processes and routine tools and techniques of the painter’s ‘craft’. In the age of mobile phones and smart devices, artists can and do still tack postcards to their studio walls. Gordon reminds us of the interiority, privacy and idiosyncrasy of the studio in a culture of instant and pervasive imaging.

The paintings within the paintings are almost all landscapes – and this is where Gordon most strongly departs from the quodlibet tradition and makes it his own. Is this re-presentation of landscape a melancholic or nostalgic gesture of something lost, ironic commentary on painting’s pretensions, or a quiet affirmation of the modest ambitions of painting? To frame a landscape painting is to draw our attention to it, to pose it as a question and to present it as a sign. To treat landscape painting as a subject of still-life might be seen as a statement on landscape’s historicity, on the pastness of the genre. In any case, it is to problematize its self-evidence as a subject for painting.

In Jacob’s Dgream, the ‘subject’ – a copy of Tintoretto’s 1577 painting of Jacob’s Ladder, itself painted to be seen di soto in sù in The Scuola di San Rocco – is almost completely obscured by the cluster of ephemera – postcards of other artworks, sketches, even paper aeroplanes - taped onto its surface. Again, this is an intriguing complication of the status of painting’s history, a distancing that collapses into a representation of painting’s construction, and perhaps even a comment on the exchangeability of all genres and images as material for the contemporary artist. We see this curious levelling of painting’s erstwhile heroism and grandeur also in The Bewitching hour, where the energetic, gestural painting of trees is levelled by the masking tape, the blank pieces of paper, and the humorous insertion of the unruly black cat.

Despite their extremism, the extremity of their technique and ritualism, Gordon’s quodlibets present as modest gestures in relation to some of the more spectacular modalities of contemporary art. Their anachronisms – of the affirmation of skill, of a world that bears no explicit trace of the incursion of the digital into our lives, of the reproduction of images as an utterly manual enterprise, of the project of hyperrealism itself within the contemporary technological circulation of images – function as understated and indirect provocations. They remind us that of the multifaceted ways in which the contemporary discourse on painting, and painting’s own intervention in its discourses can be sustained and problematized afresh.