DEAD RECKONING

Dead Reckoning is the process of calculating your direction by using a previously determined position. It is thought that Dutch sailors threw dead bodies overboard to calculate their future route. This seemed apt for a solo show in my 50th year in 2020. It’s not about looking back, it’s about looking forward. Some hope amid the cynicism. I’m trying to make the viewer look longer and harder, to have a one on one relationship with landscape painting; to make them curious and find some joy. The places depicted in my work are partly an invention, full of contrasts and spontaneity. They combine memories of places I have lived or longingly imagined, an idea of a place and the melancholy of longing and wanting to belong. An unfashionable romanticism grounded in the act of painting.

Gordon Dalton 2020

HOPE AMID THE CYNICISM

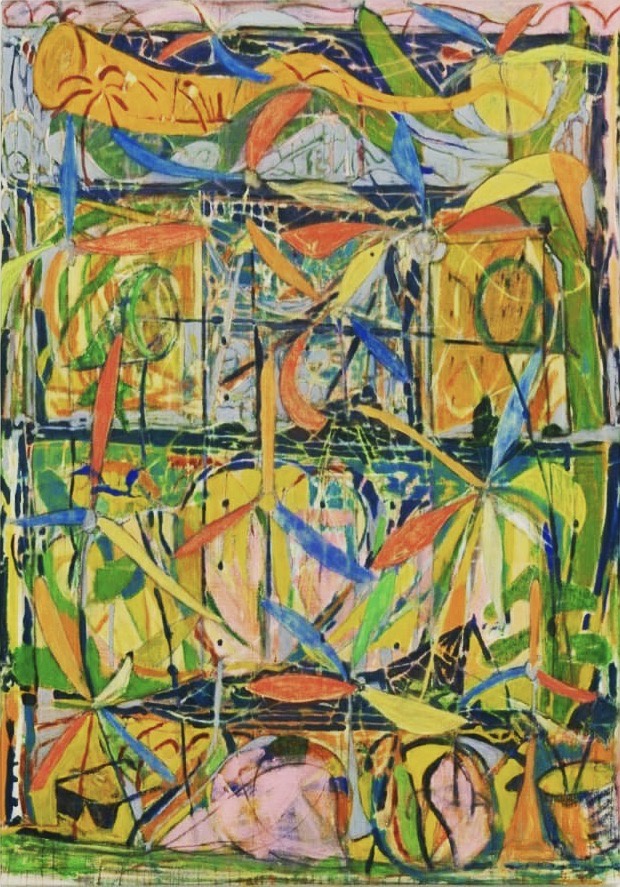

What do we see when we approach Gordon Dalton’s paintings? We find some of the tropes of landscape painting: we look past deciduous trees, through to what seem to be Victorian outbuildings or post-industrial relics. Motifs in the distance are brought forward, partly due to the use of the vertical composition and the portrait aspect ratio of the canvas. Between the trees and the buildings, space breaks down into a mix of abstracted shapes and stratifying forms that help create a unified plane.

When looking at Gordon’s work, I find myself drawn to separate elements, checking spaces and shapes, trying to decipher their function and how they affect the painting as a whole. When attempting to ‘read’ or place the ideals of traditional landscape onto Dalton’s work, the painting claps back, creating an unsteady footing, leaving an unsettling, sometimes eerie or melancholic disposition. In his painting we see distance shortened, the painting almost affronting or overbearing us with painted information over the entirety of the canvas. This maximalist trait immediately makes me want to consider Dalton’s practice in an entirely abstract manner, but I am grounded in place in a way reminiscent of works by Pierre Bonnard.

His paintings are often, but not always, based on real, mostly empty places, such as the now redeveloped Buenos Aires Zoo. Dalton visited the defunct zoo in 2016 during an artist residency. Many autobiographical real-life places and objects appear in Dalton's work, sometimes just in suggested form or as half remembered shadows. These elements are liable to mutate as the painting is created, and visual motifs come in and out of focus.

We find elements of the natural and post-industrial Teesside landscape, plumes of smoke from factories or perhaps cigarettes, empty buildings, waterways man-made and other, birds and wildlife through to bare winter trees. Dalton’s earlier work focused heavily on these motifs and, looking back over past work, I see an artist finding his subject and letting it fight with the viewer. These motifs are often laced with the socio economic baggage that any artist coming out of a working-class background would possess. The paintings were made to be cynical of the art world - they didn’t ask to be liked - they asked whether the motifs contained within them are of any worth.

Out of this painted cynicism and vitriol, we see an artist who is more internally critical; the cynicism is no longer outward-facing. We see someone who is working with a type of trepidation that comes out of building an admiration for the function of painting, its importance and history. We see abstract paintings constructed from memory. They are not merely made to articulate a space or place; their elements mutate into forms and shapes that can handle paint, hung upon the surface, the grime of paint shimmering but at other times fractured, craggy and fallible. Paint is smeared, removed, scrubbed and pushed into the grain of the canvas. The application of the paint articulates the subject and the inadequacy of memory appropriately. The half remembered place is inevitably melancholic.

In the studio, remembering and reimagining the world, I immediately think of other artists who worked in a similar fashion, artists like Édouard Vuillard, Walter Sickert or Edvard Munch. The influence of these artists is obvious - we can find references in pallet, texture and subject - but the link I am thinking of is more visceral. When I find a painting engaging it is often because I can feel the artist working, looking, pushing and sometimes failing.

I alight at works where the painter is fighting to articulate something. It is this grapple I find present within Gordon’s work. I see a surface worked, pushed and pulled with genuine interest; a slow brawl against inevitable self-doubt and the pull of cynicism.

Liam O’Connor, April 2020