Q1: Congratulations on your recent virtual solo exhibition 'Birdhouse Blues' with Aleph Contemporary, which has now toured to France showing with Atelier de Melusine. Looking at the title-piece '˜Birdhouse Blues' and some of the other landscapes, there is the appearance of grids, fragments that blur the foreground with the distance which for me creates a sense of confinement. Can you tell us about that?

GD: Hi, Thank you. Like a lot of my work, I'm trying to fit what would normally be in a landscape format into a portrait format, to give some sense of tension or as you say, confinement. This means a lot of playing around with horizontals, verticals, etc., which gives a grid effect. There is a lot of layering of horizons lines so you have many vantage points. In more simple terms, there's the effect of looking through a forest or overgrown, abandoned landscapes. The strong green and pink jolts you from top to bottom. It was taken from a Milton Avery painting.

Q2. In 'Life is Hard that's why no one survives' the complex, interwoven landscape feels like a fantasy land, the palette is joyous, but then there is a sense of melancholy, as referenced in its title. Is this a place you have been or come from?

GD: 'Life is Hard...' was the largest painting for a long time, and the first as a landscape format. This freed up a lot of space for some of the motifs. I'd moved back to Teesside after lots of years in South Wales. Sometimes these motifs can get blurred, covered up, but they are more obvious in this. There is a joy I hope but also a melancholy. Lots of abandoned industrial buildings, coastlines, boats, birds, quite clichéd subject matter but i am attempting to reclaim those landscapes, which is impossible, futile. I guess there is a sentimental nostalgia there, a romantic notion grounded in the messy business of paint.

3. I am drawn to Flamingo Land (2020), it has to a happy childhood memory. Birds, including swans, are a recurring icon in your work, can you tell us about that?

GD: They started to appear in the larger work, trees became birds, birds became clouds, shape shifting from one thing to another. There was a point when I thought if it looks like a bird let it be a bird. Let it be a boat. They work great on a compositional level but also as popular entries into a painting. There's an element of metaphor for some, others they just work for the painting itself. Flamingo Land was a zoo I used to work for in the summer holidays. I used to stare at these birds a lot. So graceful, exotic, balancing on one leg and stuck in a zoo. And they are great to draw. The swans are similar in some ways. You are battling with quite an iconic shape, trying to embed it in the painting.

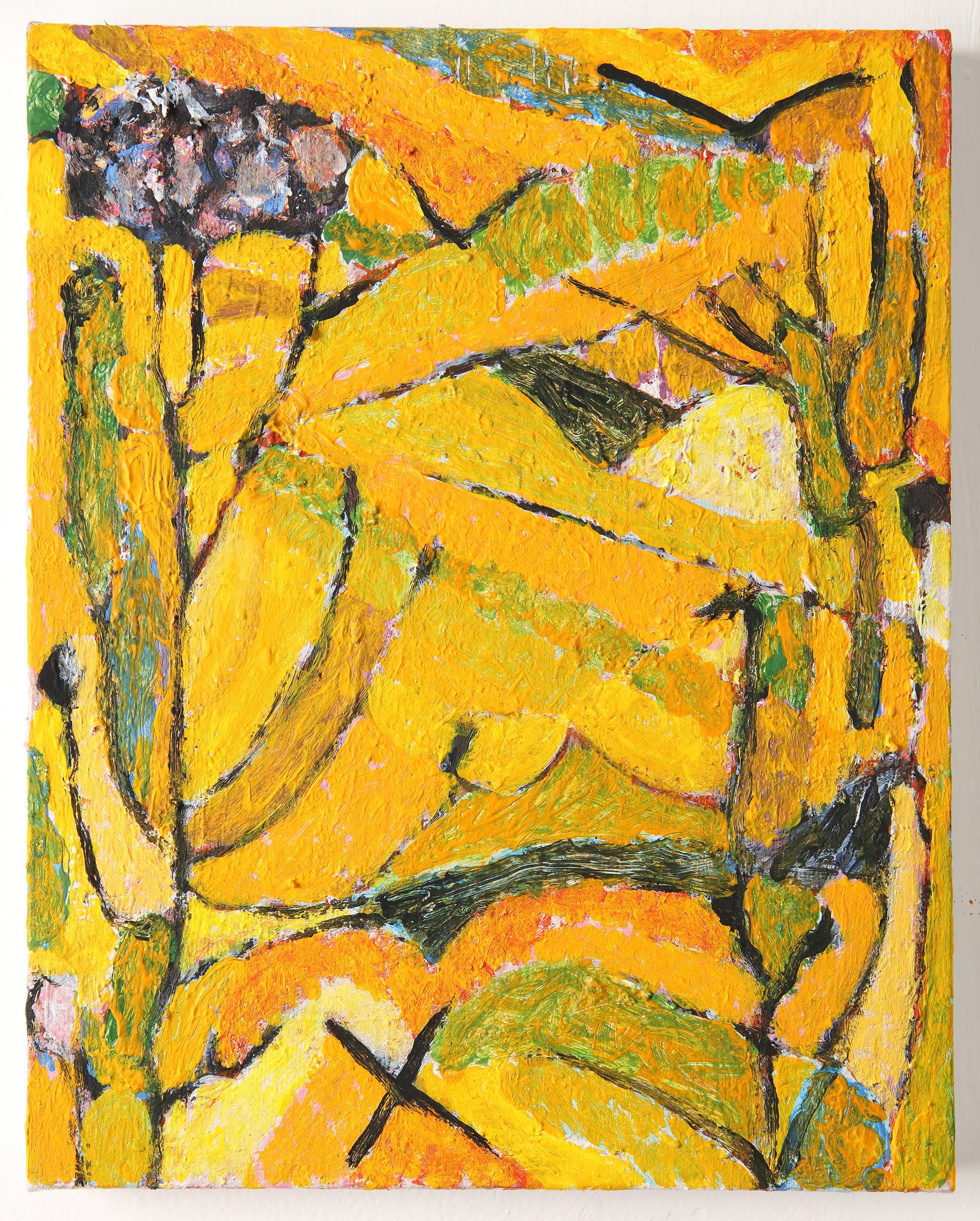

Q4. Can we talk about process - your distinctive use of paint, the thick layers and lines, luminosity of colour, at times quite abstract and other times more figurative - can you tell us about that?

GD: There's a lot of initial underpainting , usually in very bright pinks and yellows which then I paint into to play with composition. This changes constantly and a painting can change its over all colour very quickly. You're looking for something to emerge out of it. Sometimes it's obvious, sometimes it's not. You're trying to trick yourself. Throwing in a giant flamingo came from that. Then all of a sudden it will come together and then you're trying to make it exist as an object. 'Adverse Camber' (for example) was very red and orange right up until the final day when those different tones of yellow seemed so right and so wrong.

Q5. Lastly, can you tell us how you have been coping working in lockdown? Have you made it to your studio, and have you found the #artistsupportpledge helpful?

I'm ok, family is ok. My wife works for NHS so I've been struggling with home schooling a 6yr old and doing endless zoom meetings. I lost my studio half way through so like a lot of people working from kitchen table. It's not that different from how i work. I often spend months, if not years working on the smaller works, probably longer than the bigger ones. This builds up a lot of visual muscle memory. They're not studies for larger paintings, but when you get to a 3 metre canvas instead of 30cm, it can be quite scary, daunting. I like that. It's like starting again; 'What the Hell am I gonna do with this?'

Originally published on: https://www.theartfive.com/