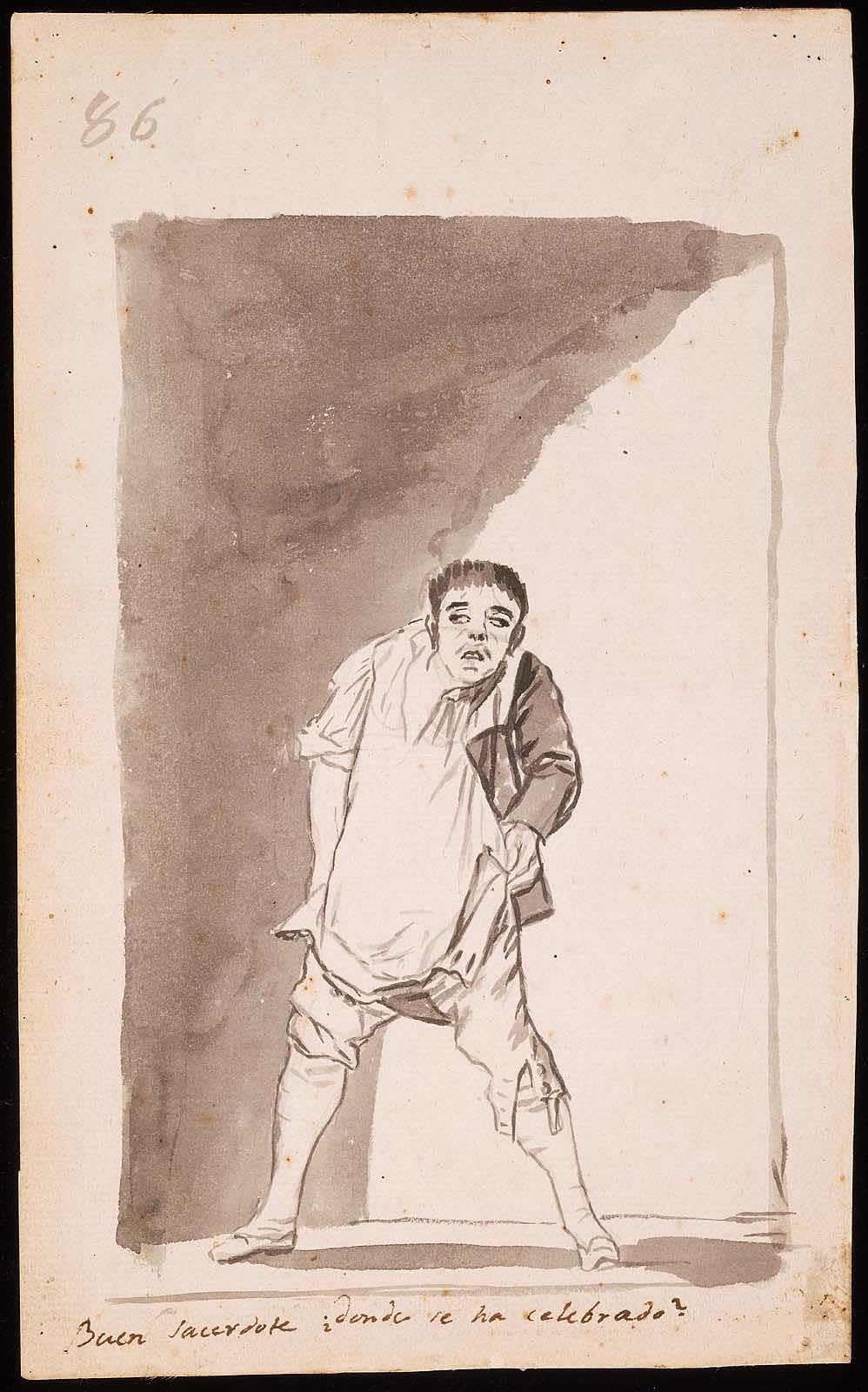

Francisco Goya: 'Good Priest'

‘In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.’

– Bertolt Brecht, motto to Svendborg Poems, 1939

‘Art is a lie that makes us realise truth.’ - Pablo Picasso, 1923

FRANCISCO GOYA, ’MEETING ON THE WALK’ 1795-96, PRADO MUSEUM

Goya’s work comes out of an era in which it is relatively easy to see how important etiquette, manners and shallow moralism were – it was constantly necessary to maintain a veneer of social normality and dignity; it was essential to accept and adhere to social hierarchies; ill-advisable to speak out against them. Lip service was vital currency; it had to be paid. Men still wore wigs and powdered their faces. It was a requirement to be seen to view the church as upholding the highest moral standards. If prostitution took place, it was done under the pretence of a more respectable meeting. If poverty and inequality were rife, its victims were either to blame, or they were sheepishly considered ‘blessed’, in order to absolve the social order of its guilt. If soldiers killed innocent people, they were able to do so whilst maintaining their moral stature. Due to the uneven, unequal structure of society, superstition and ignorance, as well as mercenary opportunism, were widespread. Social ‘order’ maintained itself through an elaborate system of bluffs and double bluffs, virtue signalling and backstabbing, all of which Goya understood and knew how to read fluently. What was revealed versus what was concealed, what was loudly asserted versus what remained unsaid, yet implicit. Goya talks constantly about this dual reality in his work– what is apparent and what is seen on the surface, along with how things are at their core- how things really are. It is worth remembering that Goya’s scepticism and ambivalence towards modern bourgeois social relations and civilisation predate those of Nietzsche, Marx and Freud.

Today we live in an age in which we are largely unaware of the continued ordering of society according to moralistic norms and flimsy etiquette – of how there is a disparity between our idealised image of the world, and how the world really is. Our society is extremely similar to the one that Goya lived in. Goya is important because he can help us to conceive of this upside-downness of society in its current state. What starts as a delicate, carefully observed, aesthetically sensitive recording of etiquette and social customs, turns, across Goya’s oeuvre, into a devastating, indignant sarcasm – an assertiveness which exposes all of the chatter for what it really is. There is so much to talk about in his drawings and paintings – at times he can be laugh-out-loud funny; at other times he can be deadly serious. Illustrator, printmaker and painter who cuts to the core of human relations, Goya also subverts traditional notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

Goya is a modern Artist in a typical sense. His inventions are expertly deployed in awareness of people’s appetite for entertainment, satire, spectacle, eros and bloodlust. There is an elegant simplicity to them. When looking at some of Goya’s drawings from the Madrid sketchbooks onwards, into the Caprichos and Disparates drawings, one might be reminded of any scene from Pasolini’s film ‘The Decameron’. The frivolous, almost-innocent atmosphere and the gentle picturing of relaxed leisure pursuits are there; the frank, confrontational depictions of poor people and those disfigured by hard work; so are the subtexts of violent self-interest, human greed, trickery and death. In ‘The Decameron’, when Andreuccio, a rich merchant, visits Naples, he is met by a beautiful young woman who claims to be his sister and invites him to stay with her. Excited by the possibility of sex, he makes himself comfortable in her house. Upon going to the toilet to relieve himself, leaving his belongings in the main salon, he falls through the ‘trapdoor’ flooring and into a stinking cesspit. When he finally escapes into the street, covered in shit, he calls up to her to let him back into the house. ‘Who are you? Get out of here you disgusting, filthy man!’ comes the reply. The penny drops: he realises he has been robbed. Later in the story, a ruined Andreuccio is forced by two robbers to steal a precious ring from the tomb of an archbishop. Upon climbing inside the tomb, he pockets the ring and calls out to the waiting robbers ‘It’s not here. Someone must have already taken it!’. The robbers slam shut the stone lid of the coffin leaving Andreuccio trapped inside, left for dead. Within half an hour, two more robbers come to try to steal from the tomb. Upon opening the coffin lid, Andreuccio bites the hand of one of the robbers; they run off, terrified by the thought of an avenging, undead archbishop. Andreuccio leaps out of the coffin with the ring, ecstatic at having become richer in Naples than he ever was before he arrived.

Goya’s lively sense of irony develops in these sketchbooks. Here his work can be seen in a quotidian, diaristic way, close to an artist like Thomas Rowlandson or Hogarth. It anticipates comic book art and cartoons, as well as caricature and satire.

He understands the disparity between people’s professed motives and their real ones. He critiques, above all, human relations in an era of capitalism: the greed and hypocrisy of the church; of the whole system in which prostitution takes place; the falseness that social customs and the keepingup-of-appearances necessitate. People in his world are motivated by sex, money and power. A gang of monks lurk, laughing and drinking beer, next to an enormous barrel. ‘No one has seen us’, the text reads. A drunken priest pulls up his trousers after consummating an unknown sexual act. A prostitute and a client meet in a park, but it looks like a perfectly normal encounter. An old man, hobbling along on crutches, peers out from a broken face: ‘This is how useful men end up’, the text reads. Sometimes Goya implies things in the image itself; at other times the brutal punchline comes in the written title. One priest, decked out in a mitre, impresses onlookers by walking along a tightrope. ‘If only the cord would break’, writes Goya. Needless to say, the cord breaking would shatter the pompous illusion of piety. An image of a mother cradling her child reads, ‘A good woman, it seems’ - we are left to imagine who she might have slept with, and for what recompense. What veils need to be lifted today? How can we discern what people’s real motives are?

Looking at the ‘Disasters of War’ series is like looking at Robert Capa’s photographs of the bombing of Madrid by the Luftwaffe during the Spanish Civil War. In 1936, Edwin Lance, a British diplomatic representative, called the bombing of the city centre by night ‘the most appalling crime in human history’. The aquatint etchings say ‘This really happened’. They implicate you. They ask ‘Why?’ Perhaps the images might even compel you, the viewer, to do something about it. Susan Sontag is right to assert that every contemporary war correspondent owes a debt to Goya.

Goya even plays with the act of looking in the images themselves, and with the gaze of the viewer. “One Cannot Look”, one caption reads, next to an image of a garrotted prisoner, killed whilst praying. How could so called ‘civilisation’ have allowed this to happen? Thematically, all of this work anticipates Dada: in the place of the aestheticised, we are given the real; the profane. In the place of whole, idealised bodies, we are given dismembered ones. In the place of the pure and the autonomous, we’re given the truncated, the compromised, the fractured. The idea of a picture with a message about happiness, conviviality or social harmony (as explored so thoroughly in Goya’s earlier Tapestry Cartoons) is replaced by one about castrations, rapes and mass graves.

In the present day, unnecessary wars have not stopped. British made bombs fall on civilian populations in Yemen. Militant Hindus are massacring Muslims in India. The United States threatens totally unprovoked war with Iran. Israel threatens extermination of the Palestinian populations in Gaza and the West Bank. Syria’s civil war has left it completely crippled; refugees are being turned away at the European border. Right-wing populism is on the rise in Europe. This, in much the same way as Goya bore witness to the irresistible military tyranny of Napoleon and its accompanying atrocities, and as his own enlightenment progressivism was threatened by the “Black Spain” of totalitarian Catholicism and the Inquisition.

In Bertolt Brecht’s play, ‘The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’, a parody of disaster capitalism, a situation arises in which having no money becomes illegal. When Jim invites his friends to a round of drinks and is unable to pay, he is sentenced to death. The choice for the other characters in this parallel, yet clearly recognisable, universe, between being poor and actively contributing to the unjust system, is clear. Jenny, his partner, sings the following lines:

‘In this world, you must make your own bed

And no one will show you the trick

So lie down and get kicked if you want to.

As for me, I would rather stand and kick’.

FRANCISCO GOYA, ’CHARITY’, 1810-14, PRADO MUSEUM

Tickets are sold for Jimmy’s trial and a murderer, who is tried before him, is able to bribe his way out of his sentence. Once Jimmy is sentenced, he is refused even a glass of water as he is led to the electric chair. The play ends painfully, as he is killed, with the funeral march and the city in chaos; protesters in support of the law demonstrate with placards emblazoned with slogans like ‘Freedom for the Rich’ and ‘Nothing you can do will help a dead man’.

Goya, like Brecht, was fascinated by people’s self-interest and unthinking conformism. He helps us to lift the veil on a totally unjust world. Reality can be so tragic and unjust as to actually feel like a parallel, unreasoning universe. What is reality? Is that other, upside-down, universe not more apt to describe it? Why do the poor and minorities always have to suffer? Why is it always backed by a consensus of ignorance?

Goya is particularly critical of the same sort of herd-mentality and mass hysteria that could bring the inhabitants of Mahagonny to wilfully execute Jimmy. He is acutely aware of the violence of ill educated populism and the wrath of the mob. Superstition, accompanied by a pious suspicion of Science and the Enlightenment, was commonplace in Goya’s Spain. Sketchbook C depicts people being tortured; victims of the Inquisition. One victim is publicly shamed ‘for having been born somewhere else’ whilst another is tied to a rack ‘for having discovered earth’s movement’. Has the woman been garrotted ‘for being a liberal?’ Goya asks in another haunting image.

Perhaps an even more astounding facet of Goya’s thought is his awareness of his own impartiality; how his view of things is acknowledged as only one part of the totality. An important forerunner to Goya, Domenico Tiepolo, painted a fresco entitled ‘The New World’. In it, a crowd of people are gathered round some kind of entertainment-novelty. But we can’t see what the thing they are gathered round is – all we see is the clamouring. Truth, for us, the viewers, is precisely our obscured, partial view of things. In another Goya drawing that dates from the period of the Caprichos a comparison between two different, but related, ways of looking, is made. A man peers through a hole in a camera-obscura like device, for viewing busy scenes, called a ‘Tutilimundi’ (a device which we know Goya knew how to use), in such a focused way that his trousers fall down. A woman, who crawls along the floor behind him, gazes, in turn, at his exposed behind.

What do we do, then, with Goya’s images of hungry winged dogs and hooded monsters? After all, this is where he really gets going, where his blood pumps fastest. It makes him seem like a sort of Gothic Fantasist – a precursor to Mary Shelley or Edgar Allan Poe. Or a film director like George A. Romero or Robert Wiene. He has the appetite for theatrical horror-fantasy of rock bands like Black Sabbath or the Misfits. These images have little to teach us about society, but we get one hell of a visual kick out of them!

So far, I’ve talked about Goya as a thinker rather than as a maker. Or as a voyeur– a ‘slipping glimpser’, in the words of Willem de Kooning. You might be forgiven for thinking that Goya’s place in the historical cannon rests on what he painted rather than how he painted it.

The reality is that Goya, in his development as an artist, came to inhabit a visual culture big and broad enough for him to be decisive in his own direction, in terms of both form and content. In any case, new content necessitates new forms. And so, the drawings have this confidence, this forthrightness, this unflinching quality. In anticipation of Abstract Art, he paints like a dancer, with grace and poise. He appears to have total control over both the abstract composition of his pictures and their narrative – he is both a master painter and a master storyteller. When one’s eye moves around the patterning of marks deployed, one also traces the peculiarities of a scene or grouping. He does it with all the empathy and psychological insight of a contemporary photographer, and with all the technical invention of Abstract Expressionist painting. He is so consummately both Abstract Painter and Social Commentator. From the tiny ink sketch into the ten-foot tall History Painting, details in Goya are subsumed within whole sweeping movements; whole passages of ink and paint. These movements seldom exclude the refinement of the particulars; equally, the details never fall out of the overarching schema or assume an undue priority. The same is true in someone like Schubert. He composes delicately, but neither the most tightened, nor the freest parts, ever fall out of the forceful whole. In both, a momentum is maintained which propels the piece into life and lucidity. The whole is dynamic and alive. Furthermore, like in Schubert’s late piano Sonatas, Goya mediates expertly between savagery and delicacy – he is capable of great outpourings of violent emotion, in his big gestures, staining the canvas with black, and also capable of profound constraint and control – delicately feathering the highlights of a face or painting in the intricacies of the lace of a mantilla.

Interestingly, in the early Tapestry Cartoons, in which he paints contemporary Spanish customs and pastimes, Goya makes full use of both tonal range and temperature range. Paintings which use predominantly dark colours appear diffused with light. Some of his lighter paintings have these sudden, savage moments of blackness. ‘Paseo de Andalucia’ goes to the very peaks of bright sunlight and right down into the depths of heavy shadow, in a balance between green and red. ‘The Straw Doll’ thrusts an airborne, inanimate corpse into a genteel genre scene and yet somehow he manages to disguise it. The black paintings are all the more devastating because of their deliberately redacted colour. In them, the figures are hacked in with the consummate, desperate confidence which in Federico Garcia Lorca’s words ‘makes Picasso look like a child’. They are to unreason and despair what Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel is to beauty; they are yet to be surpassed.

In the end, it is what Goya destroys in his blackness; what he breaks, his deadpan sarcasm; his void, that we inherit. And his sophistication. We must be glad for the freedom that Goya has conferred on us: the ability to assert ourselves and to act autonomously. The ability to think the pictorial and the political. The ability to take up a point of view on the world. The ability to inhabit and draw inspiration from the upside-down-ness of the world, rather than living in cloud-land. As artists, the power is in our hands.

There are a small number of more recent artists I can think of whose critique is as razor-sharp as Goya’s. One of them might be Ed Kienholz. In ‘Five Car Stud’, a walk-in sculptural installation, a group of rednecks engage in a horrific act of violence – they prepare to castrate a black man. Created between 1969 and 1972, and not shown in public for 40 years, the piece is a ferocious indictment of race relations in the United States. Another would be Gee Vaucher. In her album covers for the band Crass, she challenged the UK population’s complicity with the Thatcher government of the 1980s. Another would be Emory Douglas, graphic designer and minister of culture for the Black Panther Party, whose bold designs hit you like a lorry. Contemporary socially engaged Art practices, such as Beuys’ notion of ‘social sculpture’, or those written about by Claire Bishop, also seem to provide a way into the paradoxes that Goya throws up. The Situationists went a long way to lift the veil of society with their notion of ‘the Society of the Spectacle’. Perhaps in painting, late Philip Guston, or Maria Lassnig, do something of what Goya did. The Sex Pistols and The Clash did it. Maybe the plays of Sarah Kane, or the drawings of Raymond Pettibon, or the ‘auto-destructive’ Art of Gustav Metzger, do it.

One notable and relevant development was Hannah Black’s open letter to the curators of the Whitney Biennale in 2017. The letter called for the destruction of Dana Schutz’s painting ‘Open Casket’, a painting based on a photograph of the remains of Emmet Till, an African-American who was horrifically lynched in Mississippi in 1955. The letter convincingly renders Schutz’s painting as a form of opportunistic virtue-signalling and the white, bourgeois Art World as a place in which content (in painting) can never be anything other than a superfluous talking-point, for consumers. It appears to turn Goya’s notion of a sarcastic gaze back on itself. Initially, I questioned why Black chose to attack an artist whose intention was to break the cosmetic cloak of the world, rather than choosing one of the countless artists who actively contribute to it. A David Hockney or an Alex Katz seemed like a more worthy target. It surprised me, given Black’s affirmation about the power of subject matter, that she didn’t have more faith in the truth-content of the original image to educate. Nonetheless, her rightness resides in her assertion of the less-innocent history of the gaze in relation to images of violence – the one in which racist whites in the American South bought photographs of hanging black bodies as souvenirs of the lynchings they took part in. The impassioned violence of her call for the painting to be destroyed speaks to Goya’s foregrounding of injustice. It serves as an important lesson about how images of violence, like Goya’s, should be approached and used. As Susan Sontag asserts, when the subject is looking at other people’s pain, ‘no ‘we’ should be taken for granted’ - the danger of violence as a kind of pornography is everpresent.

In the Art-historical cannon, Goya’s place is somewhere in the tangled mess of pre-20th century painters who anticipate modernism. He is up there, in amongst the very best of them: Manet, Delacroix, Gericault, Blake, Bruegel, Moreau, Corot, Titian, Rembrandt, Turner.

Later painters like Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Bonnard seem infinitely more modern. The task they had – to rethink how to make sensitive, new Art in a thoroughly modernised, mechanised world, was immense. Often when we think about early modernist painting, we think of those painters as ‘breaking’ the form of painting and doing away with the past. With Goya, we see that when they inherited it, it was already broken – their role is perhaps more constructive than we assume. The answers from them about how to make beautiful Art are plain to see, but the question has changed. Today, we are almost unconsciously modern; filled with hubris. Perhaps Goya’s painted thoughts presage the cataclysms of the First and Second World Wars; the Holocaust and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as much as they anticipate the paintings of Matisse. Who can say what Goya would have thought about Contemporary Art and its facilitating institutions? Some of the questions so flatly raised by Goya need to be revisited. After all, technology has advanced so much, but society, arguably, hasn’t. Goya knows something about social engagement; human empathy. About suffering and hypocrisy and greed – how it demands a response. About how the truth is not immediately apparent. About Eros and Thanatos.

People look at paintings differently. I look at Goya like you might look at Matisse. I have a friend who thinks that Goya’s ‘Drowning Dog’ has been misinterpreted. It’s not drowning, he says. It is Goya lying six feet in his grave, looking up. And the little dog is peering over the edge of the precipice...

Francisco Goya, 'Hidden Treasure' 1824-28, Prado Museum

FRANCISCO GOYA, ’TO THE MARKET’ 1812-20, PRADO MUSEUM

Suggested Articles

-

"Francisco Goya: The Artist Who Bridged the Classical and Modern Worlds"

An overview of Goya’s life and artistic legacy.

Read more on The Prado Museum -

"The Horrors of War: Goya’s Disasters of War Series"

A closer look at Goya’s stark and powerful etchings depicting the atrocities of war.

Read more on Smarthistory -

"Goya’s Black Paintings: A Descent into Darkness"

Explore the haunting works Goya created late in life, reflecting his disillusionment with humanity.

Read more on The Guardian -

"Francisco Goya and the Art of Social Commentary"

Discover how Goya’s works critique power, greed, and hypocrisy in 18th-century Spain.

Read more on Artsy -

"The Legacy of Francisco Goya: Father of Modern Art"

A discussion on Goya’s influence on modernist painters and his pivotal role in art history.

Read more on The Collector -

"Susan Sontag on the Power of Goya’s Disasters of War"

An analysis of Goya’s impact on war photography and visual culture.

Read more on The New Yorker