What is a gesture ? Why does it become so important to modern painting, especially in the works of Matisse, and what kinds of gestures does Matisse employ ?

A gesture is spontaneous, physical , tied to the body , beyond the control of the ego. It has a kind of physical reality that marks it as separate from an idea , from premeditation. It embodies what existentialists used to call immanence. The gesture ,from Van Gogh onwards , is seen as a way of getting inside the subject , as opposed to being outside it in an objectified relationship.

‘From a certain moment on, what takes place is a kind of revelation – it is no longer me. I no longer know what I’m doing, I identify with the model’(1) Matisse said in 1908. Again , forty years later : ‘I shan’t get free of my emotion by copying the tree faithfully or by drawing its leaves one by one in the common language, but only after identifying myself with it.’ (2) And further , Matisse compares himself to a spider that ‘throws out … its thread to some convenient protuberance and thence to another that it perceives, and from one point to another weaves its web’.(3)

Something about modernity leads artists to employ the gesture as a form of authenticity, albeit one circumscribed by corporeal limitations. Yet this spontaneity is always in relation to some overall structure , and this placement might lead us to question its truth claim. Does the gesture originate from something internal, or is it a performance ?

In 1946 , Matisse had the experience of being filmed painting for a documentary. When he saw the film, Matisse was disturbed: "There was a passage showing me drawing in slow motion … Before my pencil ever touched the paper, my hand made a strange journey of its own. I never realised before that I did this. I suddenly felt as if I were shown naked – that everyone could see this – it made me feel deeply embarrassed. You must understand, this was not hesitation. I was unconsciously establishing the relationship between the subject I was about to draw and the size of my paper."(4)

The gesture is spontaneous, but Matisse was disturbed by the revelation that its placement was unconsciously calculated . His friend the French psychoanalyst Lacan saw this revelation as demonstrating that the gesture is not a bringing together of the mind and body, but instead signifying a traumatic splitting of the subject. In putting himself so immanently into his own drawing, Matisse is also separating himself from the real world. In a sense he's facing the paradox of painting : why would one want to separate oneself from actual reality and replace it with an artificial one, even an artificial paradise? Yet as Lacan liked to point out, this is also an existential paradox because we are all somehow born into language and separated from the world because of it.

Painting is haunted by its own fakery and Matisse's paintings are no exception. There is a side to painting that might be called uncanny; a world of shadows, a loss of the real, figures that are merely ghosts, doppelgängers and zombies. All painters have to find a way to overcome the medium's own paradoxes and contrivances, its inherent artificiality. Perhaps the notion of kitsch is art's equivalent of human self- delusion; many people are content to live in a bubble , but we all recognise the value of stepping out of the comfort zone.

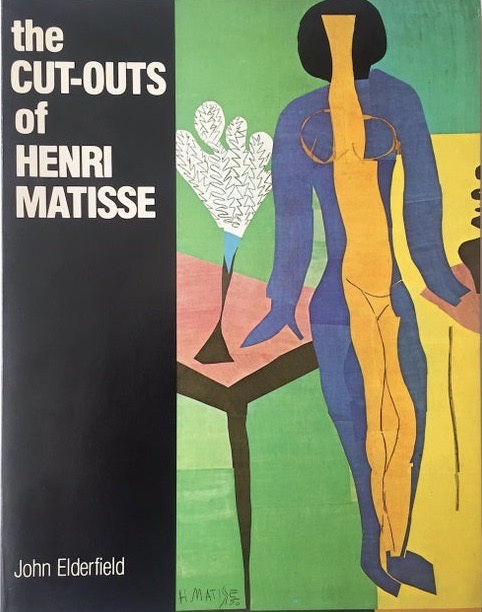

For me, Matisse seems to be able to create the illusion (is it an illusion?) that this inherent alienation can be overcome. In his late cut-outs, Matisse seems to throw off the contradictions he was dealing with all his life, between natural spontaneity and artificial calculation.

He is able to be entirely spontaneous in his cut line which he described as sculpting in colour. He would cut into paper his assistants had painted with gouache , in an endless flow which would generate flowers, leaves, birds and figures. Then he was able to place the forms in relation to each other, to move them around within the field of the painting.

This was more revelatory than drawing , because in drawing one mark follows the other. In drawing you can go back in and erase and shift around but the secondary marks are always in relation to the first marks. In collage, everything happens at once, and every element can be shifted in relationship to each other. The work becomes an embodiment of pure relationship. In contemporary terms, the relationship of collage to drawing is bit like that of relational aesthetics to performance art.

In recognising the shift from drawing to collage, a shift from a hierarchical form to a relational one, it is tempting to equate this with a movement from the masculine to the feminine, as though in his late cut outs Matisse is finally integrating the masculine and feminine sides of his personality. This may however fall victim to equating the feminine with an ego-ideal, a mistake that studying the work of Louise Bourgeois or Maria Lassnig can rectify! For me, all I know is that there is something in Matisse's cut outs that I need, and I look at them in the Tate catalogue almost every day, like a dehydrated man bending to drink from an oasis.

When I visited the exhibition of Matisse Cut -Outs at Tate Modern, I wondered how the hell Matisse managed to get so good at gluing. John Stezaker once advised me that the best glue for collage is Pritt-stick, but even with a nub like that I cannot stop myself making a mess. In none of Matisse's cut outs was there a single crease, tear or smudge of glue. Of course the reason was that, after his death, the compositions of his cut outs were meticulously traced, and the papers were glued together and mounted onto canvas by a high end picture restorers in Paris. They did a perfect job, and preserved these works forever. Matisse finally achieved perfection, but only through a division of labour.

Whilst he was making his cut outs, they were held together with pins, like the ones his wife, whom he was now separated from, had used to make hats, as she was one of the finest milliners in Paris. Matisse had sleepless nights worrying the cut outs would fall apart, that the pins would drop out and the pictures would be ruined. The relation between positive and negative space in the cut-outs was so precise that any movement in the placement of the forms would destroy the total effect of the picture. The pictures are created purely out of one shape in relation to another all moving simultaneously. For this reason, his ambiguous masterpiece, and my favourite work, "The Snail "(1953) in Tate , could not be painted: it could only be achieved through collage.

Matisse's cut outs are for me the most revelatory works of the twentieth century. To borrow a word that Lacan was fond of , they embody a total jouissance, a total joy in life, like the title of his breakthrough painting, "Le Bonheur de Vivre "( 1906) . They were made in the last seven years of his life, where he was confined to the bed of his apartment in the Hotel Regina in Nice, often in pain as he very slowly passed from stomach cancer. He completely transcended his illness through art, creating an alternative space for himself that is as close to nature as any painter has ever got.As he once said, "There are always flowers for those that want to see them ".

Dan Coombs Feb 2020

Follow this link to Matisse cut outs exhibition at Lady Lever Art Gallery

Dan Coombs, 'Bathers' 2016, 90 x 120 cm

Dan Coombs, 'Unfolding Man' 2019. 150 x 200 cm